"The very premise of writing a review on a 1980s arcade game today may seem a little silly and unnecessary, however this is not the case: it is good." – Ms. Pac-Man review, 2003

I lost interest in computer games around the time people stopped calling them "computer games," but when writing "consumer reviews" became my £1-a-day job as a penniless teenager and then student, I got plenty of mileage out of digging up the classics (and less than classics). When those ran out, and I needed a steady stream of fresh topics to write about to keep up the momentum, I cracked open the 16-bit ROM library to see what treasures or otherwise lay therein.

Here are 79,000 words of inherently unhelpful game reviews written for dooyoo.co.uk between 2000 and 2010, mainly concentrated in the middle of that span.

Nearly all of them are much too long and go into more detail than would be strictly necessary even if the games weren't obsolete, because waffling on meant higher ratings and more chance of getting a coveted crown (£1.50!) from the majority of people who didn't actually bother to read what they clicked on and mistakenly equated quantity with quality.

I apologise for the occasional interruptions by "modern" (i.e. late 1990s to early 2000s) games. Most of these are early abberations before I set myself straight and clogged up the site with worthless product suggestions just for me.

Key:

Amiga games (31)

PC games (10)

Sega Mega Drive games (27)

Super Nintendo games (3)

Sony PlayStation games (5)

Sega Dreamcast games (3)

A

The Addams Family

Kooky

Written on 04.03.07

****

The high profile remake of ‘The Addams Family’ in 1991 spawned an inevitable 16-bit video game spin-off that, as was customary for all such titles, bears such a tenuous relationship to the film that it can easily be played without having knowledge of the storyline. This also means that the biggest fan of the movie can comfortably avoid this game for eternity, without feeling like he or she has missed out on a great piece of tie-in merchandise, as it doesn’t add anything to the experience.

The game is called ‘The Addams Family,’ the box sports the film poster, and the characters have the same names. Beyond this, there’s nothing that gives off a distinctly pungent Addams Family whiff, and this could easily be the template for any generic horror-based platform game. Bizarrely, this games looks more like an adaptation of the 1960s TV show rather than the film, from the appearance of Gomez in a pinstripe suit with a likeness that’s more John Astin than Raúl Juliá (though the graphics aren’t up to much) and Thing’s confinement to red boxes rather than the newfound freedom the helpful hand gained in the feature film. It seems very strange that such a game should ignore the revamp and risk alienating the young players whose experience of the family is likely restricted to the film. There isn’t even the excuse of rushing this out for release before the film was properly developed: this game was released a year later, in 1992.

With the film’s plot ignored (which focused on the return of long-lost Uncle Fester), this game starts from scratch with the arcane nuclear family’s everyday life disrupted. In a plot that’s more than a little reminiscent of Super Mario Bros., as well as pretty much every cartoonish platform game released between 1987 and 1993, the player must travel across varied terrain in a number of areas with the goal of rescuing kidnapped family members at the end. Lacking the luxury of character selection, the player controls Gomez Addams, a pint-sized, large-headed caricature of the man of the household. Gomez is controlled with the Amiga’s joystick, and can be moved left or right, and can jump to reach higher platforms. When in possession of a ‘beanie’ – red fez hat with a propeller, that really has nothing whatsoever to do with anything – Gomez can fly for a limited period, necessary in reaching otherwise impossible areas such as the roof of the Addams’ mansion, and avoiding a nasty death over lava. Each level is intended to represent a different part of the Addams’ mansion, from underneath the garden/graveyard to hallways, the dining room and the ridiculously long boiler room, and each contains individual enemies that can be dispatched with a Mario-style bop on the head. If they have a head, that is.

The graphics are fairly basic 16-bit fare, and there’s nothing that tries to impress aside from the start menu screen, which attempts to reproduce the film’s logo and ends up emphasising the limitations of the format. Gomez and the other human (?) characters are drawn in an exaggerated manner comparable to that of the similar adaptation game ‘’Allo ’Allo: Cartoon Fun,’ but it’s quite noticeable that the enemy designs don’t fit in too well. Partly thanks to bright colours, it’s always obvious whether a sprite is an object that can be collected, such as dollar signs or the flying fez, or a beastie that will take one of Gomez’ three life hearts. As for the sound, the music in the interior levels can get pretty annoying as the faux-organ score repeats endlessly, but there’s a nice contrast in the exteriors where the music is more subdued and some convincing wind effects dominate. The sound effects are the least inspired aspect of all, and not a lot of thought seems to have been put into the ‘bop,’ ‘quock’ and ‘ding’ effects that accompany the limited range of actions. Players who die frequently, as I always did, are treated again and again to an organ synth of the Addams Family theme tune every time they pass on, which I’ve now been conditioned into expecting to hear when I kick the bucket for real.

Despite all the criticism I’ve given, this was actually a very enjoyable platform game, and one which I remember fondly from the Amiga 1200. The enemies and levels are what can be expected from a horror themed game – flying skulls and bats swooping from above, walking trees and werewolves below – but the design of the levels themselves makes gameplay interesting. The majority of the game is very confined, and though hearing Gomez quock as he hits his head on the ceiling can get very repetitive, this invites a degree of strategic thinking, especially in uncovering hidden areas. By contrast, the ‘default’ location outside the mansion is the perfect junction between levels, although not all can be reached from here, and is nicely expansive. Even though they sometimes lack logical sense, the levels are nicely varied, and the game is satisfyingly challenging rather than frustratingly difficult. Experienced players could likely complete the game in a relatively short time, but it takes a while to learn the layout.

Taken on its own merits as a platform game, ‘The Addams Family’ was one of the better realised such releases for the Amiga, and is very similar to its excellent contemporary ‘Yo! Joe’ as well as ‘Superfrog,’ the Amiga’s attempted answer to Sonic and Mario. The attempt to flog this horror-style platformer as an Addams Family game is quite weak, and in fact, I’d rather consider it a stand-alone game about a well manicured vigilante in a purple pinstripe suit exploring a creepy house and emancipating prisoners. Unfortunately, that damn death music has been so drilled into my head that I don’t think such escapism is possible. As a successful attempt to translate the old Addams Family comic strips, sitcom and film to the video game format, this gets one star, and only for not featuring that god-awful rap mix of the theme song that played over the end credits. As one of the most entertaining Amiga platform games, it scores significantly higher. It’s just a shame you couldn’t play as Lurch.

Aladdin

From Agrabah Rooftops

Written on 04.06.07

***

The inevitable 16-bit video game tie-in to Disney's 1993 film really holds no surprises for players familiar with other releases of the time such as 'The Jungle Book,' 'Pinocchio,' 'Ariel: Disney's The Little Mermaid' and later 'The Lion King' and 'Pocahontas,' including anything featuring Mickey Mouse and that bunch. Virgin once again set about translating Disney's feature film fairy tale to Sega MegaDrive format in the form of a platform game starring the story's main character, and adapting (or where necessary, making up) the plot to accommodate eight or nine levels of platform hopping and enemy busting.

In truth, the 'Aladdin' game is among the better of those listed above, and as a high profile, high budget game, it is consequently well designed and clearly well tested. Fans of the film will be thankful that the character designs are very faithful, even if the platform game format requires significant departures from the plot in many ways, including the seemingly endless cloning of the same three or four palace guards throughout. It's bright, colourful and doesn't appear rushed, but this is essentially a short-term money-making attempt by Disney and Virgin that doesn't seek to push video games forward, but is rather content to steal successful ideas from elsewhere. If not for the nice graphics and animation, there would be little to distinguish this from the countless run-of-the-mill platform games produced in the late eighties and early nineties.

The plot of the game roughly follows that of the film, although the major events are explained in-between stages by brief dialogue exchanges. The stages themselves are essentially areas that need to be successful navigated from one end to the other, although the second and third levels require specific items to be found for progress to continue. It's obvious that some aspects of the Disney plot are more suited to this style of game than others, such as Aladdin's introduction thieving from the 'Agrabah Rooftops' or the fast-paced flying carpet escape with the lamp from the 'Cave of Wonders,' while others such as the magic carpet ride with Princess Jasmine are conspicuously absent (the Princess herself only appears briefly in a couple of storyboards between levels). Elsewhere, entirely original sections such as the 'Desert' and 'Inside the Lamp' are introduced to better demonstrate the progress of the plot in game form, and to provide an excuse for some zany genie antics.

One issue with the game is essentially true for most platform games, in that there's an awful lot of repetition. Not only enemies, but recognisable obstacles appear again and again even in seemingly unrelated levels, and it's only really the madness of the 'Inside the Lamp' and 'Escape' levels that provide a vastly different playing experience. The last level in particular is disappointing, as it re-uses objects from multiple levels and assumes players won't notice if they are coloured gold, rather than dark blue. In terms of the gameplay itself, the large Aladdin sprite is more frustrating to control than the smaller heroes of other notable platform games, such as Sonic, Mario or even Superfrog, his wide stance making it very difficult to accurately leap onto falling or retracting platforms in areas where fast movement is essential.

The close focus on the character similarly makes it impossible, in many instances, to know what's coming next, and a common occurrence in the game is the 'leap into the unknown' off to the right of the current screen, which will mostly result in landing on a previously unseen platform, but can sometimes spell death. Thankfully, the generous helpings of extra lives and continues mean that the game can be mastered quite simply through a learning process as stages are repeated again and again. Aside from the basic left-to-right platform elements, the game manages to stay memorable by introducing mini-games, featuring Aladdin's simian sidekick Abu, and a pot luck, fruit machine type round at the end of each level, fuelled by grinning Genie heads the player has collected. A shopkeeper also springs up from time to time, even inexplicably in the depths of the magic lamp, where red gems can be traded for extra lives or continues.

The game is controlled with the MegaDrive joypad, and the controls, which can be changed on the Options screen, can be mastered within mere seconds of gameplay; the C button is the jump button, as with most but not all games of this type, while B will swipe Aladdin's sword in front of him, and A will throw any apples that have been collected. A combination of both these attacks is most successful for traversing the game, and later boss enemies, including the final opponent Jafar, can only be dispatched with fruit, which is generously replenished in these stages. Upon starting the game, the player is overloaded with information in the form of a static screen detailing every power-up and interactive object in the game, including Genie vase restart points and Abu bonus level tokens, but many of these are either obvious, or can be learned after playing a couple of levels. There's really no need to get out a notepad and start scribbling down that a blue heart balloon replenishes health.

The game music is a nice touch, comprised of a mixture of primitive synthesised variations on songs from the Aladdin soundtrack and original, generic pieces that evoke a 'Dungeon' or 'Desert' atmosphere. Particularly memorable are the renditions of the genie song for the 'Inside the Lamp' level, which noticeably lacks the addition of Robin Williams' singing, and themes used for the Agrabah rooftops and marketplace. There is a limited use of voice sampling for Aladdin's triumphs and disasters, and for enemy deaths and taunts, which is executed impressively free of the hissing and muffled distortion that befell many games of the time that attempted to feature human voice ('Altered Beast' remains the most hilarious example of quite poor execution).

As a player with a casual hatred of all that Disney stands for, but simultaneously a casual fan of generic retro video games, and more importantly someone who had the film on video when he was a child, this is probably the best job that could have been done in translating the film across mediums, providing a fairly interesting and compelling game that will satisfy fans of the film, which I never really was. In any case, there's nothing funny about me reviewing 'Aladdin,' it's far from the most embarrassing Disney film tie-in for a twenty-one-year-old to be playing. I never played the 'Little Mermaid' game for instance, and anyone who said I did is lying. [Stealing a Richard Herring catchphrase.]

Advantages: A reasonably faithful, good looking adaptation that could have been a lot worse.

Disadvantages: Awkward to control in places, and endlessly repetitive.

Alien³

Game Over, Man! Game Over

Written on 16.08.07

*

16-bit video game adaptations of contemporary films never made for the most memorable gaming experience, and Probe’s translation of ‘Alien 3’ lives up to the cash-in standards of the time by being largely irrelevant and unfaithful to its source. If anyone really remembers the third Alien film after all this time (the sort of film that creates quite a buzz when first released that soon dies down as audiences realise it really wasn’t that good compared to its predecessors), it once again starred Sigourney Weaver as the sci-fi action heroine Ellen Ripley, facing her third attack of terrifying H.R. Giger-designed extraterrestrial menaces in a run-down prison complex out in the galactic fringes. Using only the limited, outdated technology at their disposal, the prisoners and guards alike attempt to track down the beast with the aid of Ripley’s experience, before it inevitably kills them one by one.

The third Alien film was a disappointment after the excellent first film and the fun second outing, and the game version even more so. Released as usual across all the popular formats of the time – the Sega MegaDrive, Super Nintendo, Commodore Amiga and less advanced equivalents of each system – the game of Alien 3 was clearly designed, like many of these games with a fixed release deadline, with little knowledge or interest about the actual plot of the film, relying instead it seems on promotional trailers and photos to incorporate Ripley’s commando look and the general idea of the setting. Produced, predictably, as a side-scrolling shoot-em-up, the player controls Ripley across a number of industrial and alien terrains with the objective of rescuing captured humans and proceeding to the exit to the next level. Evidently based much more on ‘Aliens’ than Alien 3, Ripley is armed with an assortment of weapons in complete contradiction to the latter film, and the base is plagued with seemingly endless alien menaces rather than the solitary and different-looking adversary of Alien 3.

Of course, this is just a mindless shoot-em-up, and the target audience of children and young teenagers isn’t going to care how faithful it is to the film, but the game still fails to distinguish itself from the overcrowded market of similar products. The gameplay is incredibly repetitive throughout, running from right to left, up and down ladders and ducts and blasting the emerging aliens along the way, and it’s frustratingly hard like most shoot-em-ups to prevent the player from completing it successfully and ending up disappointed. Using the example of the Sega MegaDrive version, the controller’s A button switches between Ripley’s arsenal of a machine gun, flamethrower, shotgun (or maybe some kind of bazooka, I can’t tell), and hand grenades, each accompanied by a reminder of how much ammo is left, additional rounds being scattered liberally around the game area. The B button fires the selected weapon, and the C button performs a jump. The directional buttons perform as expected, moving Ripley left of right accordingly, while the up and down functions prove more useful than in many games by guiding Ripley up and down ladders, aiming her weapon in either direction, activating door opening panels and crouching.

The game screen is quite a jumble of information, most of which is essentially useless. Present as ever is the score counter, pointless unless playing competitively on an arcade machine or against a friend, and the usual counter of lives (automatically set at three, but which can be set anywhere from one to nine on the options menu) and energy, top-ups for the latter being obtained from medipacks. Most frivolous of all is the radar feature in the top right corner of the screen, which registers the presence of nearby aliens or captured humans only when they’re already in sight on the playing screen. This ridiculously limited range makes this feature entirely useless – it was clearly the game designer showing off – especially as any time spent looking at it tentatively will likely get you attacked by the blue dot that suddenly appears once the alien is on top of you. Each level also has a time limit of four minutes which is fair and keeps things moving, and a counter of the number of humans left to ‘rescue,’ which simply entails walking in front of them to make them fall to the floor and vanish.

In terms of the graphics and sound, this is just another among countless games that fails to stand out from the crowd, entrenched firmly in the average range. You can tell the main character is supposed to be Ripley because she has a shaved head, and the aliens are obviously aliens because they look kind of similar, even if the proportions and details are a little off. Otherwise, the backgrounds, objects and collectables might as well have been borrowed from any of the similar games around at the time, and were likely modified very little from the generic templates used by the graphics team. The sound effects are bland, unconvincing and uninteresting, the most distinctive being the simulated shout of ‘ugh!’ whenever Ripley is hurt that couldn’t sound less like Sigourney Weaver’s voice. The music is the usual tedious background electronic stuff that largely goes unnoticed, apart from in the game’s brief opening animation (plagiarised completely from the original 1979 trailer for ‘Alien’), when a menacing thrum is replaced with a ridiculously out-of-place jazzy title theme. Fans of retro video game music will leave disappointed.

Probe’s adaptation of Alien 3 did its job to an entirely mediocre and minimal degree, providing a further piece of merchandise to benefit from the film’s profits. Very rarely were such franchising games worthwhile and enjoyable in their own right, and more often than not, as with this one, they bore very little resemblance to the film they were supposed to be imitating. I’d recommend you avoid playing this no-longer-available video game, which ought to be a very easy task indeed in 2007.

Advantages: SNES version features the above quote in the relevant place (even if it's from the wrong film).

Disadvantages: A very weak, uninspired and irrelevant cash-in.

Amiga in general

A Bit of Fun

Written on 11.10.03

*****

I must stress that this review is not intended to persuade you to go out and buy an Amiga computer, as you might as well save your money. [That's the general disclaimer out of the way.] This is mainly intended for nostalgia purposes, for all those people like me who were brought up on the old computer games and still love to play them.

The Amiga was one of the most successful, and probably the most advanced, home and office computer before the big Windows 3.1 boom, and as such demands respect. Its 'Wordworth' word processor and 'Deluxe Paint' animation and drawing packages were unbeaten at the time, and allowed me to develop creativity very early on. music making programmes such as 'Octamed' allowed my brother to make funny sounding tunes before realising he had no interest in furthering a musical career, and the later models even had limited internet capability. but we don't care about that, let's go on to the games!

The Amiga still resides in my family's kitchen, and is often a very enjoyable alternative to the PC... but only when that's in use. There are very few modern computer games that I find worth my while playing, I'm much more a TV series guy, but the Amiga games still hold appeal. I think the formula must go something like this:

Nostalgia + simplicity + pretty rubbish + someone's using the good computer = fun!

From the platform games such as "Zool" and "Arabian Knights" [Sic] to the detailed adventure games "The Secret of Monkey Island" and "Simon the Sorceror" [Sic] (I still play these on the PC as well) and even to some of the sport games which I usually hate, the good thing about the Amiga 600 and 1200 computers was that copied games were very easy to come by. In fact, goin through the disk boxes it was a chore to find games with official covers that didn't have sticky labels and biro writing on. Oh yeah, I forgot "Golden Axe," fantastic! My dad's Amiga obsession of the late 90s also led to him buying several Amigas for very low prices, along with an unhealthy amount of games. These didn't get played much though, as the nostalgia part of the formula was missing. That Bomberman rip-off where you play as a man's willy got a few plays though, ha ha. [See: 'Bomb'X.']

Don't go and buy an Amiga to use as yuor computer, you'll be lucky if it manages to load your homepage. If you already have one though, or similar old computers such as the Amstrad, Spectrum and Commodore 64s, why not celebrate by pulling up a chair and playing Pacman or something? Some legends will never die, long live Amiga! Except I think it's technically died.

Advantages: More enjoyable games, Very cheap, Also pretty good wordprocessors and paint programs, etc.

Disadvantages: Well, it's not as good as a modern PC is it? 5 stars all the same!

Animaniacs

Only Adequately Zany

Written on 13.08.06

***

Konami’s video game tie-in to Warner Bros’ self-aware cartoon series is as conscious of its fictional status as the show itself, beginning with the characters discussing their relevance to the video game format. Animaniacs is shown to be more than a standard platform game right from the onset, an enjoyable quasi-puzzle game that makes full use of the three playable characters, each possessing different vital abilities ala ‘The Lost Vikings’ or ‘Cyberpunks.’

With their monochrome features and dated attire, Yakko, Wakko and Dot look like rejects from the early days of animation. As the cartoon series explains, that’s precisely what they are; locked for eternity in a water tower on the Warner Studios lot, from which they are prone to escaping. In the opening animation (which, technically speaking, is nothing spectacular), Yakko tells his siblings of his plan to open a hip pop-culture shop, for which they will need famous film props. Cue a variety of game stages based on recognisable films, all ever-so-slightly different to avoid copyright infringement.

The game involves three characters, but can only be played by one player. All three characters move at the same speed and jump to the same, slightly ridiculous height, but each is capable of at least one distinctive special move that is essential to progress through the game. The tallest, Yakko is able to move wooden crates when encountered, providing access to higher areas or preventing death over pits. He can also bop enemies with his bat-and-ball. Wakko is armed with a huge comedy mallet, which can push switches, break blocks and interact with large obstacles, while Dot blows kisses that cause most males to become enamoured and immobile, regardless of their species.

All of these special moves are simple to accomplish, despite some areas requiring precision, such as Wakko’s block-breaking. Once the player gets to grips with the characters’ abilities, and proceeds through enough examples, the solutions to each ‘puzzle’ become immediately apparent. The rather sexist nature of Dot’s value, merely as someone to kiss and distract men, is fitting to the era that ‘Animaniacs’ seeks to parody, but it’s debatable whether this was an intentional decision by the game’s designers…

After a brief practice stage escaping the water tower, which features several of the game’s many irrelevant cameos by other characters from the cartoon series, the player is given the option to select the desired stage. Each of the stages is of relatively equal difficulty depending on the player’s abilities (I always found stage 2 the hardest, but my brother disagreed), and divided into a number of sub-stages. If the characters die, either by losing all their health or falling to their doom, gameplay restarts at the start of the sub-stage rather than the beginning of the entire level.

The Sega MegaDrive game utilises the A, B and C buttons of the joypad, but almost completely neglects the ‘up’ and ‘down’ parts of the directional pad, which are only useful when making selections. Left and right move the characters in either direction, and progress through each stage always moves from left to right. The basic controls are set as A for action, B for jump and C for change, but these can be switched on the options screen, as can the game’s language.

The four respective stages are ‘The Adventures of Dirk Rugged VII’ (based on an Indiana Jones-type character), ‘Space Wars’ (you know that one), ‘Swing ’em Low, Hang ’em High’ (a generic western) and ‘Bloodmask: Part 32,’ intended as a parody the ‘Friday the Thirteenth’ Jason films, but incorporating all the stereotypical elements of classic haunted house horror. Each stage features appropriate enemies, occasionally from the cartoon series itself, such as that fat warden guy who likes to catch the Animaniacs in a net. Despite losing points for originality, as every level is generic and predictable in lampooning a genre, the premise is saved by the ever-present subliminal hints that these are all merely studio sets, complete with lighting rigs visible in places and the occasional camera or clapperboard dotted around the landscape. That’s studio sets with real alligators and real kamikaze spaceships.

As with all 16-bit cartoon adaptations, the graphics are acceptable and believable as they don’t need to strive for realism. It’s disappointing that no actual animation was created for this game’s introductory sequence, which instead only features moving mouths on static character faces and their speech blipping up as different-coloured text, but the in-game movement animations are nice enough, if still a little static. The game lacks a little coherence between the style of the characters taken directly from the TV series, and the random enemy creatures and landscapes created especially for the game, resulting in something of an uncomfortable mix of two styles that could have been avoided with a little more artistic care. The music is fun and enjoyable, despite repeating endlessly as all MegaDrive music did, and several different, appropriate pieces appear within each level and sub-stage. There are no character voices, aside from some strange synthesised squawks when they get hit.

‘Animaniacs’ is fairly difficult, but fortunately the game incorporates a password system. This can be access straight from the title screen, and is based on a 3 x 3 grid of the three main characters’ faces. Each time a level is complete, a password is given based on the levels accomplished so far, and the player’s remaining lives. This means that constant repeated play-throughs of the same tedious levels can be avoided, leaving more time to concentrate on those that you either avoid, or have previously found too difficult.

The characters move fairly slowly, and this becomes a little irritating at times, although the majority of the game is spent in enclosed or moving areas so it doesn’t prove much of a problem. The major frustration lies in the specificity of certain puzzle solutions, causing players to wander round in circles again and again in repeated attempts to strike a set of blocks from exactly the right distance. Time is a factor, and unlike most platform games which provide a greater time limit than necessary, it’s a frequent occurrence that every second counts in this game. Thankfully, extra time items can be picked up in most of the offending areas.

A successful adaptation of the show’s spirit, ‘Animaniacs’ would probably not hold up so well if not for the cheap trick of the self-conscious stuff, but I like that. It’s more than a simple left-to-right standard platform game with a cartoon character’s head superimposed, and although the plot is equally pointless, the game’s trickiness leads to very satisfying results once difficult stages are cleared. The game is repetitive after a while, indicating something of a rushed or half-bothered production, and it’s annoying seeing the graphic artists try to squeeze in as many meaningless and distracting characters from the TV series as possible, rather than incorporating them properly into the gameplay in place of the arbitrary obstacles (Pinky and The Brain do nothing more than scurry across the bottom of the game screen in the second level).

The Sega MegaDrive version differs greatly from that made for its rival the Super Nintendo, and disappointingly the Sega version is inferior. The Nintendo game featured similar character tagging, but the three could interact with each other to pass obstacles, the opening water tower scene actually held some relevance, and there was a greater focus on secondary characters. All this is lacking from the Sega version, but as both follow different plots, the Sega levels are at least unique to the format. ‘Animaniacs’ isn’t a great puzzle game, nor a great platform game, nor a flawless cartoon adaptation, but something in-between. At least it’s better than all the Disney ones.

Advantages: Intelligent gameplay.

Disadvantages: Repetitive and limited, and pales in comparison to the SNES edition.

Another World

Beware the Black Beast Bear

Written on 14.08.06

***

Delphine Software were one of the prominent adventure game designers of the early 90s, licensed under Virgin. Released in 1991, 'Another World' operates at its basic level like a simplistic platform game, the player moving left and right through two-dimensional areas and interacting with the environment, but the game requires a greater degree of intelligence, skill and perseverance than the standard platform fare.

Like 'Flashback,' its superior successor, this game is an incredibly tricky puzzle adventure for older players and demands an extreme degree of patience right from the onset. The most accurate label for 'Another World' is 'interactive movie.' A movie that plays the same scene over and over and over and over again until the character finally stops getting zapped. A movie for which the player has no script, unless they have access to a handy walkthrough guide.

The player is almost completely denied free will as each section must be completed in the only way possible before advancing to the next. The only freedom available is to err, and hang around trying to work out what to do before you solve it or get killed, the latter being more likely. This restriction of free will is perhaps most evident in situations where direction of travel appears to be optional, but is always directed by the next puzzle. For example, a lift that needs to be taken down can ascend just as easily- but there won't be anything of value there.

The game received critical acclaim for its unique graphical style at the time, and although it's been usurped by advances in technology, it still looks really good. The style strives for realism, especially in portrayal of human or humanoid characters and beasts. All are proportionally perfect, and movement is smooth and completely believable, based on animations copied verbatim from filmed human activity. The game never attains a lifelike quality due to the nature of the format and the time, and the graphic artists are evidently very much aware of this: all shading consists simply of one light and one dark layer, similar to an animé style, and as such all areas become rather messy, wobbly blobs. The game features a lot of cut scenes that integrate perfectly into the action by using precisely the same graphics, but from a more cinematic angle than the standard sideways presentation of the playing field.

Gameplay itself is where 'Another World' really lets itself down, and this is a big disappointment. Controls are fiddly despite being carried out through a digital joypad, and precision is constantly needed. Any time the player is struck by an enemy or encounters something else fatal, a bed of spikes for example, death is instant and the level restarts. Each level is relatively small at only a few screens in length, but there are usually several tricky, life-endangering tasks to be accomplished before progress can be made to the next. In total there are roughly seven or eight major areas, each split into a number of screens.

A deliberate choice has been made not to clutter the game screen with pointless details, and as such there is an uncharacteristic lack of any information on the screen whatsoever: no score, no inventory and no live count (the game provides infinite lives at least). This increases the cinematic quality and serves to involve the player further in the adventure, as they don’t get distracted by numerals. There is minimal emphasis on sound also, as events are communicated in actions and images rather than speech (or text), although there is a written introduction that accompanies the opening animation if the title screen is left untouched for a while. The music isn't particularly notable at any point, and the game works better in the many silent areas; you can easily play the game with a CD on in the background, though it's sometimes useful to hear whether you’ve erected force-fields successfully if your vision of them is blocked.

The plot itself is fairly interesting, and enjoyable to work through if you have the skill and patience. A red-headed professor is sent literally to another world after his particle accelerator is struck by lightning, and after surviving a few scrapes with native creatures, he is captured by humanoid aliens. The brilliantly smooth animated opening invites interpretation: was the scientist reckless? Was he trying to play God, and was the lightning strike and terrestrial exile his humbling punishment? You control the jailbreak, led by your new alien comrade, and try to find a way out of the city and into freedom. The story works consistently as the game progresses, and the ending is quite nice and not the norm for this kind of adventure. As usual in these silent games, it's actually quite easy to be drawn to certain characters despite their simplicity and lack of any real development, and I'm a big fan of the helpful, bulky alien buddy.

'Another World' is still available for emulators of the Amiga and Sega MegaDrive, and has reportedly been re-released for GameBoy Advance. The 32-bit home computer versions boast greatly superior graphics to the 16-bit console, but everything else is identical. My version is for the MegaDrive, and is controlled with the standard directional pad, and B and C buttons (A performs the same functions as B). The player can walk or run through areas, take running leaps or more measured standing jumps, and is able to fire and recharge his trusty, multi-purpose weapon after its initial equip.

The game is too frustrating to be considered a true classic, although it was doubtless influential in moving movie-style games on from 'Dragon's Lair' and 'Space Ace' in the 80s to the filmed versions that followed. If you don't mind using your brain, and then trying to do precisely what your brain tells you to do even if you die endlessly in the process, you will be able to appreciate the beauty of 'Another World.' If you are a regular human being with average tolerance level, you're best avoiding it and watching a sci-fi adventure film instead. 'Another World' is the likely origin of survival horror, as 'Resident Evil' isn't a million light years away from this, despite being about zombies rather than bald alien thugs. The overall purple and orange colour scheme is very pleasant.

Advantages: Innovative approach to graphics and gameplay.

Disadvantages: Tedious, frustrating, fiddly and far too difficult to be really enjoyable.

Arabian Nights

To Look Fear in the Fez

Written on 13.07.06

***

A couple of years before Disney’s ‘Aladdin’ imposed that corporation’s universal vision of Arabian mythology onto the world’s youth, Krysalis Software attempted something similar, only infinitely less successful and targeting only young Amiga users. ‘Arabian Nights’ is yet another one-player platform game, which was easily among the most popular and over-used formats for early 90s computer games, but succeeds in distinguishing itself as a worthwhile and entertaining use of the player’s time through friendly graphics, nice handling and dabbles in mixing game genres.

An animated opening sequence (easily skipped by pressing the joystick’s fire button) lays down the plot: the player controls Sinbad Jnr., a lowly but skilled gardener who is secretly in love with a Princess. While finishing off an impressive bear-shaped bush, he witnesses the Princess being grabbed and whisked away by an ugly, red flying demon thing, and immediately runs to her rescue. Unfortunately, the palace guards are stupid, and mistakenly believe that Sinbad Jnr. was responsible for their Princess’ disappearance. He is imprisoned in a dungeon, and you must help him escape.

Animated intros were always great features of early video games, and like most from this period, the dialogue is all typed rather than spoken, appearing on title cards between animations in a process reminiscent of silent films. There’s a damsel in distress, and her plucky, young would-be rescuer is out on his own. There’s no point dwelling on some of the stupider points of the plot as this is all just the necessary scene-setting for some simplistic platform fun. Needless to say, Sinbad’s gardening technique never comes in useful in the game, understandable as you are too busy tracking down the Princess to mess around trimming bushes into bear shapes, though Sinbad is quick off the draw with his little cutlass.

The general look of Arabian Nights is instantly reminiscent of the more popular ‘Soccer Kid,’ also released by Krysalis. It’s clear that the same art team was involved, as both Sinbad Jnr. and Soccer Kid have the self-same oversized head, but the backgrounds, setting and enemy / obstacle design are completely different, owing to the differing time periods of both games. Arabian Nights also tends to be a little more claustrophobic in terms of level design, with most areas involving vertical movement as much as sideways, whereas Soccer Kid follows a more standard left-to-right scrolling style. The graphics are colourful but measured, and there’s plenty of variety due to the multiple locations of the game, from the pastel-pink dungeon to a lush forest, sunken galleon and ice palace. The enemies are all nicely detailed with easily discernible facial features, and it’s always obvious as to which objects are background details and which are props or collectables. The game’s sound effects are fairly good, but nothing too impressive, and the music is quite energetic and fast-paced with something of a Middle Eastern flavour.

Primarily a platform game, Arabian Nights is marketed as something of a puzzle game, although the puzzles themselves are nothing too complex, perhaps targeting children of around seven to ten years. Levels commonly feature keys that are needed to progress through locked doors, and some of these are stealthily hidden, necessitating some backwards movement through the stages. A couple of one-off puzzles are perhaps a little intimidating for younger players, but many can be discovered by accident, and these are often repeated throughout levels to allow the player a smug sense of satisfaction at having solved the riddles so early. The prime example is the large pots in the dungeon level that can be entered by pulling the joystick down. The other heavily marketed aspect of the game is actually fairly disappointing, and sees a shift from platform game format to flying carpet frolics between select stages, reminiscent of poorly thought-out racing simulators. These sections are essentially mini-games, but progress through them is essential and the player’s lives can be lost to the numerous obstacles such as flying galleons and parachuting sheep.

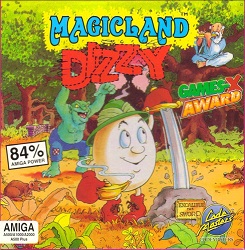

The main appeal of Arabian Nights lies in the ease of its controls, a feat that many games of the time sadly failed to achieve. As expected, two-dimensional movement of Sinbad Jnr. is controlled by the joystick’s left and right clicks, with ‘up’ for jump and ‘down’ for duck. The fire button swings the player’s sword, which only has a very limited range but can at least be held down to slice the air indefinitely. The keyboard also comes into play, with the space bar activating the glowing light bulbs that appear above the character’s head when puzzle events occur. This is a fairly small feature of the game, hardly ever coming into play, unlike genuine platform-puzzle games like the excellent ‘Dizzy’ series. Other customary keyboard commands include ‘P’ to pause the game, and ‘Esc’ to exit to the title screen. The game manual comes as standard and may be needed by players who are unsure how to use the inventory, as well as providing copy protection at the start of level two. Software pirates and thieves can play level one though; that’s fine.

Arabian Nights is a nice game to pick up and play, without the burden that comes with many modern video games. Sinbad Jnr’s fez-and-waistcoat appearance and stupid name don’t serve to eradicate Western stereotypes of mythical Arabia, and the damsel-in-distress plot is equally subject to scrutiny, but in terms of gameplay and pleasing graphics this is an above average Amiga game. The afore-mentioned ‘Soccer Kid’ is better in both of these areas, but Arabian Nights has a nice, naïve charm in its attempt to rise above being a mere platform game by introducing an inventory. Thankfully, it works, and the sunken galleon level remains one of my favourite stages from the hundreds of platform games I have on this dumb old computer.

This 16-bit game comes on a single floppy disc, and is playable on Amiga 500, 500+, 600, 1200 and 4000 machines. Alternatively, get an emulator.

Advantages: Nice, colourful graphics and varied level designs, as well as easy and enjoyable to control

Disadvantages: Puzzles are rudimentary, music is repetitive and irritating, genre encourages crap pun titles

Atomic Robo Kid

Written on 16.08.06

***

It’s a fairly bleak premise: an extraterrestrial Earth colony in the 21st century has been bombarded with radiation, and then subsequently attacked by a fleet of robots. The colonists’ only hope is a boy in a sophisticated battle suit, who must traverse hostile terrain and wipe out the intruders. Despite the emphasis on plot, and some other nice tricks that make this game stand out, it’s classifiable as standard R-Type shoot-em-up fare, as the player moves through caverns, avoids laser bullets, collects power-ups and unleashes severe firepower.

Released on the Sega MegaDrive in 1988, Treco’s ‘Atomic Robo-Kid’ is more sophisticated than the average shoot-em-up, and far more playable as a result. Gone is the constantly scrolling screen of ‘R-Type’ and ‘Disposable Hero,’ as it’s now up to the player to confront the action ahead rather than having to withstand its inevitable approach. There’s also unique incorporation of platform game traits, as the character begins the game in a standing rather than jet-propelled floating position, and can return to this pose any time by touching down on floor level. Almost all of the game involves being airborne, but there are some great advantages to wandering around on foot that prove essential as the game progresses.

Each level is designated as an ‘Act,’ and although these proceed consecutively through the game, it soon becomes clear that levels are grouped in fours. Every third stage ends in an encounter with a ridiculously enormous boss enemy, and the fourth stage consist of a more rewarding and evenly weighted face-off with another robot creature similar to the player’s character, and possessing the same abilities. Although incredibly brief, whichever way victory goes, these evenly weighted duels are perhaps the most instantly rewarding parts of the whole game.

Terrain for the regular stages varies, beginning in a customary industrial cyberpunk setting and proceeding to levels with varying degrees of strangeness, such as the inside of a body and a more pleasant rocky desert wasteland. The enemy designs are fairly consistent throughout, and are nothing extraordinary for anyone who’s played this type of shoot-em-up before. There’s an attempt to give Robo-Kid some personality at the end of every fourth stage, as he engages in a brief, typed dialogue with his CPU, using words such as ‘gnarly.’ Rad. This isn’t a puzzle game however, and the plot details they describe – such as ‘find a merchant and make an arms deal’ – have no bearing on your actions, which remain simple and laser-based.

There are a finite number of weapon upgrades that can be collected by the player, all of which accumulate and can be switched by pressing the joypad’s ‘B’ button, unlike similar games such as ‘Zero Wing’ which feature only one weapon at a time, until the next is picked up as replacement. The full arsenal doesn’t take long to accumulate through power-ups left behind intermittently by enemies, especially as these power-ups can be spun round and round by firing at them until they indicate the desired option. A fiery pulse laser replaces the stinking mediocre thing you start gameplay with, and this can be joined by a 3-way white laser, a beam ray with wide area, and a missile that can destroy enemy bullets in flight as well as break through rocks in specific areas. The game ensures that all four are effective in different scenarios, although a lot of it’s down to player preference.

Despite the sarcastic advice of Robo-Kid’s CPU that he’ll do fine as long as he shoots everything, it can be more prudent at times to try to avoid more difficult enemies if there’s a clear escape route. The player won’t actually get damaged by encountering an enemy’s physical form, only their energy weapons. As such, a lot of fun can be had switching to a standing rather than flying mode, and jumping past a load of them to lower ground. When not in flight, the ‘B’ button causes the character to jump rather than switch between weapons, and the ‘A’ and ‘C’ buttons both act as the fire button, which need to be pushed repeatedly and hastily to achieve any kind of real progress.

The original arcade game was 2-player compatible, but this feature is lacking from the home console release. An options screen allows the player to select game difficulty, which for once is automatically set to ‘Easy,’ something that should hopefully offend serious shoot-em-up fans. Changing game difficulty has no effect on the gameplay, merely increasing or decreasing the number of available lives and continue credits. As such, upgrading to the more hardcore options seems pretty pointless.

For a game originally released in 1988, the graphics and sound are nothing too impressive, but are better than less professional releases. Robo-Kid’s movements are animated nicely, and there’s a nice sense of three-dimensional playing due to the background moving at a different speed, a technique that would be perfected in ‘Sonic the Hedgehog.’ It’s a colourful and aesthetically pleasing game, but the colour schemes are always sensibly limited within each level to avoid clashing, and to allow players to concentrate on the action. The music is standard racy 16-bit techno fare, fairly annoying but strangely endearing all the same, and there’s enough variation in sound effects to distinguish between enemy attacks and friendly fire, and the different weapons in your own arsenal. I still wouldn’t recommend playing the game if you’re blind though.

A middle-of-the-road arcade-at-home shoot-em-up, ‘Atomic Robo-Kid’ is notable for its incorporation of (player-controlled) gravity. This is a game it would be fun to be great at, as the ground movement adds a nice extra dimension to play. The game should be equally appealing to children and adults, as the character is fairly cute despite being one step from a Dalek, and the colours prominent but restrained. My main gripe is the lack of a health or energy bar for the player, meaning that each and every shot brings on instant death. This makes the game a lot harder and more frustrating than necessary, and it really does your thumb joints in.

Advantages: Great use of gravity.

Disadvantages: Instant deaths make gameplay frustrating.

Back to the Future Part III

You Didn't Peach Clapa

Written on 14.04.04

*

My father is, and always will be, an Amigan. A dying race of people whose belief in and respect for the Amiga series of computers forever prevents them from entering the 21st century. As a self-professed Amigan, he was understandably hurt when my brother and I asked for a Sega MegaDrive console on which to play some popular games in 1992.

The only factor that seemed to quell his frustration was when he noticed a video game edition of Back to the Future part III at a low price, which would at least allow him to play on the new console.

Unfortunately for this Amigan, that game is terrible.

PREMISE

The Back to the Future series of films (1985-1991) concerned the friendship between a young, evolving man called Marty and an aged, eccentric scientist commonly known as "Doc" as they travelled to different points in the past and future, either by accident or honourable intent. The third and final part of the trilogy saw Marty travelling to the Old West of 1885 with the time-travelling car to rescue the Doc who, it becomes apparent, will be shot in the back unless helped. The majority of the film is tasteful Western shenanigans, and this game takes four events at random and extends them into badly designed levels.

LEVEL 1

A horse chase. With no regard for those who wish to know the film's plot, the player is thrust straight into the action as they control Doc Brown on horseback in an attempt to catch up with his beloved Clara before she plummets off a ravine.

The constantly moving player must duck to avoid crows and shots of a bandit, or jump over crates and pits. Any impact causes Doc to fall off his horse and there are three tries before game over. As well as the obstacles there are green and blue objects to pick up which can speed up or slow down the horse, but these are not essential.

This level is incredibly hard and far too fast, and in my experience playing the game I was only able to complete it by knowing exactly what the order of obstacles was. Most players will get bored with the game before they complete this level, especially after seeing the image of Clara going over the ravine at the end: if you were worrying about my spelling or sanity in the title of this review, the game is so poorly drawn in places that the message "YOU DIDN'T REACH CLARA" at the game over screen reads on a TV as "YOU DIDN'T PEACH CLAPA"- they clearly need to work on their 'R's.

LEVEL 2

At one point in the film, Marty demonstrates his 'Wild Gunman' expertise once again by shooting all the wooden ducks at a shooting gallery. The game foolishly decides to turn this into a level, in which the player must move their slow and tedious cursor over ducks and bandits, shooting them but avoiding civilians. Incredibly dull stuff.

LEVEL 3

Few players ever made it this far, and even fewer have played this level and enjoyed it. Pie throwing: sound familiar to the last level? Essentially, the player controls Marty as he throws pies in the faces of Buford "Mad Dog" Tannen's cronies.

LEVEL 4

The fourth and final level seems at last to be the start of the proper game, but in premise is identical to the first level, but on foot and not scrolling. The player controls Marty McFly as he jumps along the train and collects the seven special logs (I'm sure it was just three in the film. Well I could be mistaken. No, I am not) to shove in the furnace. This is all done under a seemingly impossible time limit and to add insult to tedium, enemies appear once again that can be taken out with, that's right, pie trays.

CONTROLS

This game is designed for use on the MegaDrive's joypad as it uses the directional buttons (up, down, left, right) and the three action buttons (A, B and C) to carry out different moves. The shooting levels are contolled by pressing any action button to fire. Despite being simple to use, these controls leave the player pressing buttons frantically and angrily, and will likely cause more controller malfunctions through a bad temper than other games.

VERDICT

This is the definition of a cash-in game, clearly brought out in a hurry to meet the film's release date and with absolutely nothing to add to the player's grasp of video game technology. The levels are boring, incredibly tedious and poorly designed, and it would be easy to leave this cartridge sitting at the bottom of a toy box to be eternally crushed by assorted, dusty Batmobiles. The Back to the Future series was very funny, exciting and original, but these games add nothing to the BTTF experience. Sorry Dad.

Advantages: None that I can see - fans of the films will be disappointed

Disadvantages: Boring, Unoriginal, Badly designed

Blockout

Another Brick in the Wall

Written on 17.08.06

***

“How shall I fill the final places? How should I complete the wall?”

Roger Waters, ‘Empty Spaces’ [I was going through my Pink Floyd phase]

When California Dreams had the bright idea of making Tetris with a Z-axis, they were probably convinced that their creation would make them gods of the video game realm. Instead, it’s remembered by most as quite an enjoyable Tetris clone that provided a bit of fun, but was too difficult to make any real progress. To me, ‘Block Out’ is yet another frustrating and addictive puzzle game to help waste my life away.

Released on Sega MegaDrive under license from Electronic Arts in 1991, ‘Block Out’ is easy to get to grips with, but fiendishly difficult to master. Unlike many games where extreme difficulty was merely a way to compensate for lack of originality, this three-dimensional puzzle game could easily spawn an elite group of players, who have mastered the three-dimensional logic. The average player will probably take a while to get past level 3.

The game screen is disorienting at first, until you orientate yourself properly. The player effectively looks down from the top of a Tetris grid, and pieces fall from directly in front of the line of sight to meet the wall at the far end. Gameplay is identical to Tetris: the pieces are constantly moving, and increase in speed as the levels progress. The player needs to position the pieces on screen, which often involves rotating them to fit, and they can then be hurtled towards the far wall to slot in-between the other bricks.

The bricks are mostly the same four-cube ones seen in Tetris, but the game is a little more lenient and introduces a couple of two- and three-cube variants, especially useful for corners. The classic ‘straight line’ brick is replaced here by shorter versions, as a length of four would do some serious damage on this game’s smaller grid. Each brick is initially red, until the player shoves a block out into the Z-axis, where it becomes orange. Each wall can only be destroyed when every square of the grid is filled, which can become frustrating if you accidentally block off a couple of holes with a block in the far foreground.

After orange the colours cycle, logically, through yellow, dark green, light blue, dark blue, purple and then back to red. In the standard game, the foremost ‘game over’ blocks will be light blue. Leaving the title screen alone, a helpful demo begins to demonstrate gameplay. Unfortunately, it does deceive viewers into thinking the game is a lot easier than it really is, as the level count never increases, and the player thus has no problem completing his red walls.

“He’s intelligent, but not experienced. His pattern indicates two-dimensional thinking.”

Spock, Star Trek II

Bricks can be rotated with the joypad’s A, B and C buttons, although it takes a very long time for the controls to become instinctive, and there’s going to be a lot of guess-work and mistakes early on. The C button is the least mind-bending, rotating pieces nice and easily through 360 degrees, but A and B are more complicated, rotating pieces in what would be the X and Y axes… if the game wasn’t seen sideways-on. The best strategy is to build flat, two-dimensional walls for as much of the game as possible, only venturing into the third dimension when a piece doesn’t perfectly fit. In these instances, players should rotate pieces until the furthest block or blocks plug the remaining hole(s), and the back wall will vanish, leaving only the remainder of the final brick.

It’s a fun game and fairly addictive, although the difficulty will eventually dissuade most players from trying again. The game becomes speedy as early as level three, and I’ve never survived past level six. In most cases, it’s clear that a couple of botched blocks in the later levels equate to a point of no return, and the remaining seconds of gameplay can be spent having some destructive fun, sending blocks hurtling towards the furthest wall, which gets closer and closer each time. The game has a score counter, which is only really useful if you wish to compete with someone by taking turns, but unfortunately there’s no ‘next block’ indicator, common to many Tetris-style games, which would prove handy in aiding short-term strategy. As it is, the game is completely down to on-the-spot thinking.

For anyone crazy enough to venture beyond the standard game, ‘Block Out’ boasts some real hardcore options. The ‘3D Mania’ option features three-dimensional bricks – I’ll clarify: that means bricks that can never be placed flat on the back wall. Oh dear – and ‘Out of Control,’ featuring similar blocks to the regular game, but extended variants consisting of up to six cubes. Oh dear oh dear. There’s also an option to build a custom level, choosing the block type and dimensions of the grid. It seems that the game designers were generous with the pre-set level, as it already uses the maximum depth of 12. The standard 5x5x12 level is undoubtedly the most rewarding, as the maximum possibility of 7x7x12 just takes too long.

If you ever compulsively played Tetris and wondered what it would be like to stand at the top and chuck blocks down, ‘Block Out’ may give you some idea. There’s a free online clone at http://www.3dtris.de/ which manages to be even more confusing than the original, but the MegaDrive’s custom joypad makes for a far superior experience.

It would be interesting to encounter any other strange attempts to change the viewpoint of classic video games. I’d suggest ‘Point-of-View PacMan’ and ‘Far Away Frogger.’

Advantages: Interesting and well developed take on Tetris.

Disadvantages: Doesn't convince me of its superiority, especially as it's far too difficult.

Bomb'X

Written on 02.10.07

**

I can picture the scene. Independent game producer Fabrice Decroix is sitting at home playing the arcade classic ‘Bomberman,’ recently released for home computer systems, breaking through blocks and working his way towards the exit in the middle. After completing all fifty levels he feels fairly satisfied, but can’t help thinking, “this game would be much better if Bomberman was a penis, the exit was a woman lying in a bed, and the whole game was tailored around the flimsy contrivance of him getting his end away.” Desperate to patent his idea before all the other eagle-eyed programmers noticed the gaping hole in the market for smutty knock-offs of superior arcade favourites, Decroix unleashed ‘Bomb X’ into the Amiga world in 1993, just in time to satisfy those who were getting fairly bored of the really terrible ‘Viz’ game.

‘Bomb X’ is a reasonably straightforward Bomberman clone that relies solely on its sexual premise for sales, though it was only ever released as a budget title. Its four-player option is a definite bonus, as each player controls a differently shaped version of the main character wearing a differently coloured waistcoat, selectable on the title screen. Aside from the default blue player, who I assume represents the male norm, there is a short and podgy character, a thin and withered one, and one with quite lumpy legs – or rather, the two appendages that these characters use for legs. All of them except the thin one wear a form of pink beret, the thin one’s skin being too taut for headwear to reveal itself, and there is no multi-racial option. Gameplay is almost exactly the same as Bomberman, as each player races against each other to destroy brown blocks with their emissions, avoiding or shooting enemies and collecting power-ups along the way. It’s very limited in appeal, but provides an enjoyable cheap laugh for a few minutes, if you’re thirteen years old, and even beyond the gimmicks it’s quite an enjoyable game.

The game lasts for an alleged fifty levels, all of which are pretty much the same; a green background, a blonde woman lying patiently in the centre, with destructible brown blocks, invincible metallic blue blocks, green trap-doors and several roaming enemies who regenerate after death. The enemies are a little abstract, one being a sort of generic germ or virus and the other a chomping set of teeth, about which players can draw their own conclusions. Needless to say, donning the protective rubber ‘shield’ (that’s what we told my little brother it was called, when he was slightly too young to really understand what was going on) protects against these germs for a limited time, though it has the side-effect of the player no longer being able to shoot.

Once the path to the coquettish exit is cleared, the player must seek out the ‘shield’ in order to enter its gates protected, and bounce around in joy for a few seconds before the next level starts all over again. In disappointing contrast to these enemies and the rubber protector, the other collectables take the form of a life-giving heart and a cake, demonstrating a real laziness. Could he really not think of anything else smutty to include instead? Collecting a pair of hotpants allows the player to race around at an increased speed, while the skull is a red herring that causes death, similar to the Robotnik monitors in the Sonic the Hedgehog games and purple mushrooms in Mario. [Insert purple mushroom joke here.]

Although it gets very old very fast, this is an enjoyable, fast-paced game that multiples in enjoyment when playing against other people. The joystick wobbles your willy around the screen and the fire button shoots his magic bullets, an extended press of the button leaving behind the all-important puddles that clear the path to the centre. Probably the best touch is the need to re-fuel every so often, demonstrated by the character becoming dishevelled and less priapic, while the race for the Johnny adds a nicely competitive element to the multiplayer experience. The sound effects are hardly worth mentioning, and could easily be recycled between any number of games, but the graphics are fairly enjoyable and simplistic, too cartoony to be considered truly offensive or explicit (in a ‘Wicked Willie’ style) but detailed enough to discern what’s going on. There is very limited use of animation that keeps the disk space low, merely amounting to the opening animation of a bloke opening his coat to reveal his un-detailed, nude body, and the bouncing around that’s somehow supposed to signify intercourse at the end of each level. The nicest little touch is the character’s dizzy spell after they receive a blow from an enemy (or rather, a chomp), as its head swings in a dazed circle.

‘Bomb X’ was released on a single floppy disk (yes, yes) and was compatible with the Amiga 500, 600 and 1200, but wasn’t hard disk installable (yes, yes, calm down). There is absolutely nothing beyond the flimsy cartoon-sex premise to distinguish this from other Bomberman clones, and in fact the array of power-ups and special features is significantly less than in the original game itself – the phallus can only shoot one blob at a time, for example. It’s amusing at about the most simplistic level possible, but what I actually enjoy about it more is the moral ground it takes in demonstrating the need for protection by forcing the player to wear it before they can have their fun at the end. It’s a bit of a convoluted advertisement for safe sex, and not one I can imagine them introducing into the National Curriculum, but if someone told you they had a Bomberman game where the player controlled a penis who was trying to have sex, you would, wouldn’t you?

Advantages: 4-player fun and very cheap laughs.

Disadvantages: Appeal is about as limited as you would expect.

Boogerman

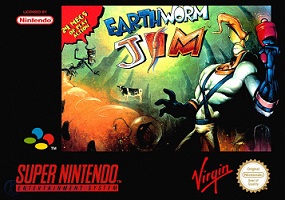

The Ren & Stimpy Generation: Fart II [See: Earthworm Jim]

**

Despite some nicely smooth graphics, ‘Boogerman’ is nothing more than bog-standard 16-bit left-to-right platform fare, only done a little worse. Published by Interplay under what must have been a fairly large budget, this ‘Pick ’n’ Flick Adventure’ relies entirely on an exaggerated toilet humour premise to appeal to the younger demographic that took so fondly to ‘Ren & Stimpy,’ ‘Toxic Crusaders’ and ‘Earthworm Jim.’

Boogerman is a super-hero who flies around on hot chilli farts and takes out bad guys with an arsenal of bodily functions: he can burp, spit, fart and flick nose goblins. Stop sniggering. Oh wait, you weren’t. I can’t criticise kids for finding the premise entertaining, despite their parents’ best efforts to raise enlightened offspring, as I remember finding the idea quite funny when I first heard about it on its original release. Unfortunately, Boogerman almost literally takes a dump on enthusiastic players with its entirely mediocre gameplay.

As is standard for all simplistic platform games, an elaborate and insignificant premise is set up to explain why the player controls a snot-flicking super-hero in a strange forest that seems to take its nutrients from a sewer. As expected it’s pretty weak; no one lost any sleep there. A ‘Star Wars’ style introductory crawl informs us that environmentally conscious Professor Stinkbaum has devised a method to rid the world of all pollution, by transferring it inter-dimensionally to Dimension X-crement. The subsequent animation shows health inspector Snotty Ragsdale accidentally sneezing on the machine one night while hoovering the lab, resulting in some contraption or other going haywire, and essentially drags him down into its bowels. The plot’s not important, it’s mainly there for the cynics, and for once it doesn’t even dictate the final villain of the game.

The game exploits toilet humour right from the start, featuring a literal pair of toilets on the title screen, one to start the game and one to input a password pictogram. Selecting either of these toilets by pressing the down button causes the depraved hero to spin into its depths. These toilets appear within the game, providing access to subterranean sewer stages underneath the regular levels, while slimy portaloos act like the star-posts in ‘Sonic the Hedgehog,’ providing a place from which to restart when the character dies. Levels such as the opening ‘Flatulent Swamps’ are perhaps not as disgusting as they might first sound, due to the cartoon graphics, but pretty much everything is covered in a layer of bright green slime.

Anyone who’s played a platform game before will pick up the controls instantly. Left and right move Boogerman in those directions, generally heading right to proceed through each level, while up and down are handy when climbing dripping vines. The down button is the more useful of the two, providing access to the afore-mentioned toilets, digging in heaps of soil to find items, and also causing Boogerman to duck in a strained position with his rear end very prominent. One of his bodily attacks can only be accomplished in this squat position.

The joypad’s ‘A’ button flicks snot from an exhaustible supply indicated by the nose-picking icon in the top left of the screen, ‘B’ jumps, and ‘C’ unleashes the burp (or, if squatting, the bottom burp). Holding the C button down for longer will release a more extreme fart or burp respectively, which can dispatch more enemies or destroy rock walls, just like in real life. Eating a chilli gives these attacks a longer range, while milk replaces the snot option with more effective saliva. If the player uses up all their snot and burp power, they’ll have to rely on the old method of bouncing on the enemies’ heads until they locate more slime.

Boogerman’s graphics are the only real area in which it impresses, although not to the extent of some of its contemporaries. The artists succeed in capturing the exaggerated cartoon style of shows like ‘Ren & Stimpy,’ ‘The Tick’ and everything on Nickelodeon ever. The main character moves with impressive fluidity, which is especially relevant on the slick landscape, and if you leave him alone for a while he’ll go through several animated procedures, based predictably on snot and farts. The enemy designs are also pretty nice, although they don’t really fit into the toilet humour side of the game, the best ones looking more like rejects from ‘The Real Ghostbusters.’ Overall, ‘Earthworm Jim’ is a far, far more impressive game.

Like EWJ, Boogerman incorporates audio recordings of voice samples, something that was fairly risky in 16-bit consoles as the results were almost invariably distorted and muffled. Picking up items causes the character to praise ‘cool’ or ‘rad,’ and every time a new life begins he announces his would-be catch-phrase, ‘Booger!’ I’ll bet whoever came up with that was crossing his fingers that it would become a popular saying in school playgrounds, but fortunately no-one really noticed. The game’s average sound effects quickly become tiresome, based as they are on slime and flushes. The music is deep and bassy and feels somehow appropriate as the soundtrack to this exploration of the lower bodily functions.

Boogerman has no real value, artistic or entertaining, but was probably snapped up by a small but dedicated minority on its release. Too reliant on the expectation that flicking bogies will make a funny game, it really doesn’t last out. I would have been at least impressed if the designers had provided more incentive to continue playing, by making later scenarios or power-ups increasingly disgusting and even X-rated as the game approaches its conclusion, but there’s not so much as a single wee-wee or number two. Strangely for a game so obsessed with PG-level depravity, there’s a noticeable lack of attention devoted to armpits, and perhaps a tad too much on noses.

Educated comedian Stewart Lee was right when he said that the funniest occurrence in the entire month-long run of the Edinburgh Fringe festival (with all of its avant-garde progressive comedy) would be an old man, by himself, doing a fart in a wood. But would you really base a video game on it?

Advantages: Fluid motion.

Disadvantages: It stinks.

The Chaos Engine

Written on 29.06.06

****

The Bitmap Brothers' 1992 shoot-em-up was a major participant in the evolution of that genre from the simplistic early space games like 'Space Invaders' and 'Galaxians' to the three-dimensional revolution of 'Doom' and 'Quake.' While still firmly entrenched in the second dimension, the playing field viewed from above, the excellent 'The Chaos Engine' is one of my all-time favourite games of the genre.

Set in a post-apocalyptic alternative past at the turn of the twentieth century, the game is much like any other shoot-em-up: the player controls the movement of a heavily armed character around various terrains, pulverising everything that moves and collecting power-ups until, eventually, they come across the over-the-top enemy at the game's climax and make things right again.

The storyline is intriguing, and the steampunk style looks very original as elements of Victorian England merge with futuristic technology. One or two players each control one of the "hard-nailed mercenaries for hire" (in one player mode, the computer controls the second character with impressive cooperative A.I.). These mercenaries must battle across the ravaged English landscape to find the source of all its disarray: the eponymous Chaos Engine, created by a mad scientist before it went haywire and morphed its creator and everything in the vicinity into savage supernatural beasts. This premise is primarily there to excuse a number of excellent and increasingly disturbing enemy designs throughout the game, from prehistoric monsters and rock creatures to huge crawling hands and insects.

The player(s) can choose between six playable characters, all of which boast different strengths. Brigand and Mercenary are middle-of-the-road types balancing out the extreme quick-witted speed of the otherwise vulnerable Gentleman and Scientist and the sluggish, thick-skinned Navvie and Thug. The character art is excellent, and along with the brief biographies ensures that players select their favourite characters based on more than just statistics - who would choose the neanderthal Thug over Navvie's winking bearded face? An unusual difference between this Sega Mega-Drive version and the Amiga version I'm more familiar with is the substitution of the perverse Preacher for the less controversial Scientist; both characters are essentially exactly the same, however the profile art of the Preacher’s dog collar has been tinkered with to resemble the top button of a shirt. The bespectacled and maniacally grinning Mercenary was another of my favourites, although Gentleman's cool, respectable air is also quite enticing.

The gameplay itself is very fun and fast, and avoids many of the common flaws with this type of game. For a start, the levels are completely free-roaming, meaning the players can take things at their own pace and even retreat completely to previously emptied areas in instances of ambush. Once destroyed, enemies (the locations of which are entirely pre-set) remain dead, but there are plenty of nasty surprises that will startle all but the most experienced player. A great aspect of the game is the shop that opens after clearing two areas (each world consists of four areas, and there are four worlds in total). Using the money that can be collected from dispatching enemies, the players can choose how to upgrade the characters' statistics, weapons and special attacks. Unlike other games, there's neither the time nor the funds to fashion a perfect superman character with maxed-out stats, and all decisions must be made carefully, tailored to the player's own strengths and preferences.

There's not much difference between the home computer and console version of this game ported to the Mega-Drive. In this, the directional pad moves the characters around in 2-D as would be expected, and holding the A and C buttons unleashes the players' relentless torrents of firepower. The B button activates the special power, which can be replenished from the shop or by finding objects in the playing field. The player has to activate a number of nodes and other hidden objects for progress to continue in each level before walking through the final portcullis.

This is really a pretty difficult game, and it takes an incredibly long time and a lot of luck to reach the finale. Players are given password codes after each area, tailored specifically to the player's stats and life count. The first forest world is by far the most aesthetically pleasing, with its varied terrain of rocks, foliage and bridged swamps, while the later levels tend to get a bit visually repetitive. 'The Chaos Engine' is still highly playable today, despite the aerial-view format looking a little dated, and can still provide hours of frustration for one or two trigger-happy players.

Advantages: Very enjoyable, Great characters add to the effect, Cheap thrills

Disadvantages: Nothing too original, Frustrating at times

Chuck Rock

Unga Bunga

Written on 07.03.07

**